Gay: In painful and insecure times like these, many of us find it comforting to re-read a favourite book – perhaps one from a sunnier and more innocent time, for the escape it offers briefly, or one that depicts characters triumphing through dangers and hardships. Children’s books that we’ve loved offer the security of an experience with a known and safe ending, the sense of hope that is typical of the genre and maybe an added richness on re-reading as we bring new experiences to our understanding of the text. In grappling with our current realities, books are essential sources of distraction, rest, mental health and inspiration.

Among childhood books I’ve re-read repeatedly, many fall into the first category of giving a sense of peace and safety. Top of the list are the Anne books by L. M. Montgomery (Anne of Green Gables and its sequels). Anne’s life, friendships, loves and aspirations are ordinary and simple, set against the gorgeous backdrop of old-fashioned rural Prince Edward Island. The solid, conventional small-town community life depicted may be parochial, but it’s also infinitely reassuring and an antidote to chaos. The same applies to What Katy Did, Seven Little Australians, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books, Kathryn Forbes’ Mama’s Bank Account, and Jane Austen’s novels. The social orders depicted have their faults and blind spots, but the heroines find happiness and fulfilling paths forward within them. These descriptions of ordinary, solid families and relationships form a reference point, drawn from the authors’ faith in humanity, which can anchor readers feeling adrift on stormy seas.

In the second category I recall A Little Princess (1905) by Frances Hodgson Burnett, a classic riches-to-rags-to-riches story that, despite being wildly improbable, contains some grains of truth: for example, that hardship can develop character but not without passage through bitterness and despair, and that friendship is the greatest balm for misery. Hester Burton’s books, for example the wonderful Time of Trial (which won the 1963 Carnegie Medal), offer more realistic depictions of strong young women passing through historical events that test and challenge them: war, natural disasters, social injustice and religious intolerance. I also recall Alan Garner’s fantasy novels, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath, as depicting children showing courage and persistence in the face of unearthly terror – unsettling books, but ones in which the protagonists prevail.

Ian: Tales of social upheaval and dislocation are a particular subgenre in children’s books and borrow from similar tales in adult literature. This is partly because the first rule of writing a story in which children are the main agents is “get rid of the parents” which is easily arranged in times of upheaval, and also because such times allow all sorts of interesting behaviours and plots that would be unrealistic in “ordinary times”. Of course war is the commonest of these situations and our generation grew up in the aftermath of the Second World War, the currency of the deeply unpopular Vietnam War and the ever-present threat of nuclear war, all of which I imagine have receded in significance for children today. I read many books set in these tumultuous times; I wonder how many are still read today? Examples include When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (Judith Kerr), I am David (Anne Holm), The Silver Sword (Ian Serraillier), Carrie’s War (Nina Bawden),Goodnight Mr Tom (Michelle Magorian), and even The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe (C.S. Lewis) which is really an escape from the frightening reality of the evacuations from London. There were also non-fiction books, the best known of which was The Diary of Anne Frank, but it’s important to remember that many of the “fictions” were actually semi-autobiographical (When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit) or based on fact (The Silver Sword). More recent books such as The Book Thief are powerful stories too, but I think that the earlier generation benefited from the fact that the war was within the lived experience of the authors, which made the representation of the world at the time both vivid and authentic. Earlier conflicts are also plentiful – Esther Forbe’s Johnny Tremain is a vivid presentation of the early events in the American Revolution, for example.

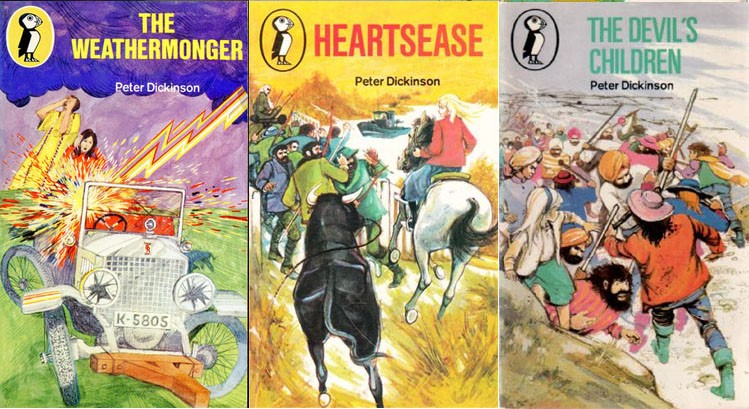

But other kinds of social disruption are encountered too, such as the unnamed events that lead to urban breakdown in Keep Calm by Joan Phipson, or natural disasters such as the storm depicted in Hills End by Ivan Southall. An outstanding example is Peter Dickinson’s Changes trilogy, in particular The Devil’s Children in which 12-year-old Nicola Gore has to cope with parents who fail to return home, and a strange new society outside where the rules of survival are being negotiated daily. In this story, the frightening sense of being relatively powerless in a world of danger has remained with me. Nicky is portrayed as somewhat younger than her years, but develops a courage and self-awareness during the course of the book – today no doubt she would be a feisty young woman from the start, but I feel that her relative helplessness at the beginning is a better reflection of the state in which most children would imagine themselves if plunged into a similar world. Feisty characters are admirable, but relatively weak characters are easier to identify with, and offer the redemptive hope that I, too, could learn to become stronger if it was required of me.

Interestingly, The Changes Trilogy was written backwards. The first novel, The Weathermonger, deals with the end of the saga. Heartsease (my personal favourite) is set in the middle period, while The Devil’s Children, written last, tells the story of the beginning of the period. Finally, as a child I didn’t differentiate much between “children’s books” and books intended for adults which were accessible enough for me to enjoy. Consequently I read John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids and Day of the Triffids, the war stories of Paul Brickhill, Brave New World, 1984, Neville Shute (A Town like Alice, Pied Piper, On the Beach) and a host of other books in which societal disruption provided the backdrop or the central events of the story.

Gay: As a child I found Johnny Tremain a revelation, both for its setting (which was my first source of knowledge about the American Revolution) and for its independent spirit. It’s another of the books I have re-read as an adult with utter pleasure: its characters, themes and writing remain fresh and universal. Australian authors like Ivan Southall and Colin Thiele were fond of tackling dark themes in the 1960’s: in addition to Southall’s Hills End, I remember his Ash Road and Thiele’s devastating February Dragon, both about bushfires. I Am David was a classic which I think our entire generation read, and which I remember for its sense of a terrifying and incomprehensible world. A decade later, Marietta Moskin wrote I am Rosemarie, a depiction of life in a concentration camp for Jewish teenager Rosemarie, which was watered down considerably but frightening enough. In a similar vein to John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids, John Christopher’s The Prince In Waiting trilogy from the early 1970’s evokes a seemingly medieval world beset by mutations and a fear of technology, clearly in the aftermath of a nuclear bomb or accident.

Ian: I suspect that to the generation of writers who lived through the Second World War, social dislocation was a very real prospect, and so the threat of nuclear war or other social disasters must have seemed all too real. After all, it’s hard to imagine a more preposterous, far-fetched scenario than the events of the Nazi era and the Holocaust. Strangely, as a child, I never imagined that war or pestilence could happen in my lifetime – those were stories from other people’s lives; they were safely in the past. I was confident that we had learned our lessons, that we had conquered all those obviously ridiculous attitudes, that such mistakes would never be made again. For some reason I assumed that while motor car accidents, for example, could and did still happen, war and pestilence were out of the question. I was consequently flabbergasted when in the 1990s, the jingoism and nationalism I had read about from the 1920s and 1930s began to reassert themselves, and I have come to see that the attitude towards war which was shared by my generation was a local thing, an attitude confined to a moment in history, to a single generation. As such, it’s important that these stories be re-told and re-told.

The severity of Covid-19 has shaken the complacency of western nations who have perhaps felt that advanced healthcare systems have defeated the old enemies such as plagues, and may be anxiety-provoking to children old enough to understand what is happening. Of course for children in other parts of the world, this world of disease may be a familiar story, though no less frightening. In my mind, stories of pestilence and disease do not feature heavily in the plots of Australian, American or English children’s books published since World War 2, even the dystopias, but this may well change as a result of the current pandemic. There is nothing like first-hand experience, or even a near miss, to heighten the salience of a dangerous situation. I expect there will be a fascination with, and need for such stories in the future, with heroes and heroines who take arms against a sea of troubles and show us the way to get through the dark and the danger.

Gay: I want to end by mentioning the last book ever written by Henry Treece: The Dream-Time, published in 1967. Treece started out as a poet in 1940, wrote a couple of novels in the early 50s, and then dedicated himself to writing children’s fiction, mainly about people with swords. The Dream-Time is a short, strange book. Following the adventures of Crookleg, an artistically gifted boy at the dawn of humanity, it’s a reminder of who we are and where we came from. Charles Keeping’s illustrations, which are often terrifying and violent, in this book are also sublimely lyrical and tender, right down to the smudged ink fingerprints that gently mould his figures. It’s essentially a book about the wellsprings of art and love in brutal, hard times. I plan to re-read it this week.

I loved the Anne books and always wanted to visit Prince Edward Island.

LikeLike

Sorry for leaving a reply so late! Yes, the books I read have given me a long list of locations to visit too!

LikeLiked by 1 person